Sun rises on Egypt's Silicon Valley

The Middle East has long been searching for its own Silicon Valley, but it’s been searching for the wrong ecosystem under the wrong name.

‘Sun City’ in Egypt might be MENA’s Palo Alto as the Cairo suburb of Heliopolis is a hub for a rising semiconductor industry that has been quietly building for the last 10 years.

Importantly, the aims of those in the sector are not to mimic its famous counterpart in Palo Alto but to be their own foundation of a high tech electronics industry in Egypt.

If it’s successful, it could have major ramifications for entrepreneurs and startup ecosystems throughout the region, churning out at home – and enticing back from the US – the kind of highly experienced engineers who were the founders of America’s tech industry.

Quiet wins

The semiconductor industry is arguably Egypt’s most cohesive and global-facing tech startup sector.

It started in 1993 when the father of the sector, Hisham Haddara, talked French company Anacad into opening an office in Cairo. It remained a small, foreign company-led chip design industry until 2004 when two Egyptian companies hit the market: Haddara’s Si-Ware and Sameh Shaheen’s rival Scenario Consultants.

Eleven years later, there are at least 17 locally-born companies operating in the Egyptian semiconductor sector, all catering to customers in the US, Europe and Asia. All are ‘fab-less’, which means they design the components, and either sell the design to customers or have them manufactured elsewhere, rather than actually making the parts in-house.

“What is really interesting today is that there is new blood,” Haddara told Wamda. “[Founders] in their 30s, doing startups, successful startups, are getting acquired by US companies and there is a community, a vibrant community.”

“I had always the conviction up to now that the electronics industry is the gateway to prosperity for countries like Egypt and has been so for so many countries over the world.”

Si-Ware founders Bassam Saadany (Left) and Hisham Haddara (right) with Yoi Yamamoto after winning a PRISM Award for Photonics Innovation. (Image via Si-Ware)

At least seven major international semiconductor companies have offices in Egypt, mostly in Heliopolis.

Sahar Selim, CEO and cofounder of microchip design and verification startup Boost Valley, told Wamda that the sector was still small in comparison to markets such as Taiwan or Singapore, but was growing “slowly but surely”.

“[Egypt is] starting to have this footprint in the international market. It’s not as big as the US market but we are starting to have this reputation that we do have those good engineers,” she said.

Furthermore, the sector is already spinning off new high-tech companies.

One example is Xonebee, a startup developing communication networks that don’t require SIM cards and can transfer data over regular landline phone connections. Its founder, Mohammad Omara, is a veteran of the US and Egypt semiconductor industries.

Electronics are where the big deals lie

The sector is also quietly racking up the Egyptian startup ecosystem’s biggest deals.

In July, Silicon Vision, one of the older companies in the sector founded in 2007, was acquired by US electronics design giant Synopsys. It’s now an exclusive design center for the $7.5 billion company, and will still be based out of Cairo.

In 2011, SysDSoft was sold to Intel, leaving founder Khaled Ismail (below) with enough cash to set up his own angel fund KI Angels.

And last year Si-Ware, closed Egypt’s largest ever tech round with a $9.5 million investment from the government-backed Technology Development Fund (TDF) and Saudi Arabia’s Taqnia.

Egypt’s small pool of investors are beginning to recognize the value of companies in this sector as well.

Xonebee was incubated in Flat6Labs in 2013, and now names Sawari Ventures founder Ahmed Alfi as a board member.

Selim launched Boost with cofounders Randa Hashem and another who she did not wish to name yet in 2012, and said they’d received funding from local venture investors, although she would not say with whom.

And VC fund Innoventures is involved in the sector, with an investment in Scenario Consultants.

The global market

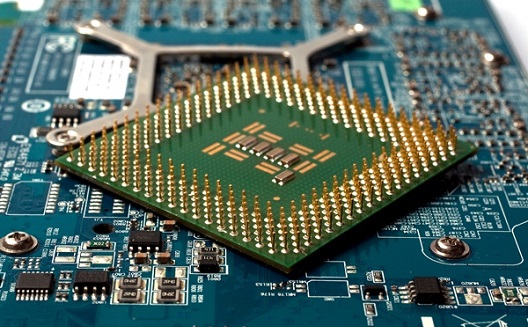

Semiconductor devices are the basis of modern electronics. They use semiconducting materials such as silicon to make up integrated circuits and microprocessors, and are the building blocks of high tech circuitry.

Gartner estimates the global semiconductor industry will touch $348 billion this year, which itself is just one part of a multi-trillion dollar electronics sector.

Moreover, as microchips become more complex and expensive, verification and testing - the kind of work Boost Valley and other companies in Egypt specialize in - as well as detailed digital design work is becoming more in-demand, according to McKinsey.

“Complex integrated-chip designs now exceed $100 million, with designs of $20 million to $50 million becoming more commonplace among more standard or basic components. Naturally these rising costs have far ranging implications for the industry’s structure, participants and value chain,” said Ron Collett and Dorian Pyle in a McKinsey paper.

In layman’s terms, that means world-class engineers in cheaper locations, such as Egypt, are gaining an economic ascendancy over their more expensively-located geographic rivals.

Challenges

Yet starting a semiconductor company in Egypt, although the payoff can be large, is not simple.

The fact the country was not known for high tech electronics was, and at times still is, a hindrance.

“[Finance] was one of the problems. In the beginning you would like to use investors’ money, so you go and knock on the door of the investors and consistently the message that you had was ‘this is not something Egypt is known for and not something we want to put money into’,” said Ahmed Shalash, cofounder of Varkon Semiconductors, now Wasiela, in 2008.

“In the beginning we were saying we are from Cairo, Egypt, and people were scratching their heads, saying ‘no surely you’re actually from India’.”

Shalash also pointed to a shortage of experienced engineers.

Egypt graduates a huge number of engineers every year in every discipline, and Selim and Haddara told Wamda separately that technically they’re very skilled.

But despite the flow of expats returning from the US and Europe, there are still not enough in Egypt who have experience in the industry. Shalash said Wasiela takes fresh grads and trains them over time, but this would put constraints on how fast his company could grow as there was little spare talent in the market.

The cost of design tools was also a problem for new companies. Haddara said few startups could afford digital design software packages costing in the tens of thousands of dollars.

Supporting a fledgling industry

These problems, however, are being dealt with, slowly.

Egypt’s semiconductor industry has an advantage over other startups sectors in that it is backed by an industry body.

EITESAL, the Egyptian Information Telecommunications, Electronics and Software Alliance, has enough clout to not only get the government to agree to a growth strategy for the sector, but also to partly fund it.

The official 2014 strategic study, led by Haddara, wants the Egyptian electronics industry to be worth $80 billion by 2030, with as many as 200 fab-less companies in the sector.

He told Wamda that to do this they need about $125 million of financial support a year for the next seven years. What they got, from a government under heavy budgetary pressure, was $12.5 million.

But even that is doing some good. Haddara said seven small companies have benefited from a program that subsidizes design tool costs, and the EITESAL Business Nurturing Initiative (EBNI) which launched in 2012.

The EBNI incubation initiative doesn’t provide any money, but does help entrepreneurs through their startup’s first three years of life.

Other support organisations include the CORPST training academy, Nile University which specializes in electronics, and the VLSI Academy which partners with universities to boost electronics training.

Shalash said he knew of a number of young engineers keen to start their own business, but right now a lack of financing stood in their way. He said programs and grants from EITESAL, the Ministry of Communications and others would take a couple of years to bear fruit but he was positive they would.

“In the beginning things were difficult, after a while more people got encouraged to start their own companies,” Shalash said “Most of them were self-financed as far as I know. Once the ecosystem improves I imagine more people will get encouraged.”